Donald Windham and Sandy Campbell

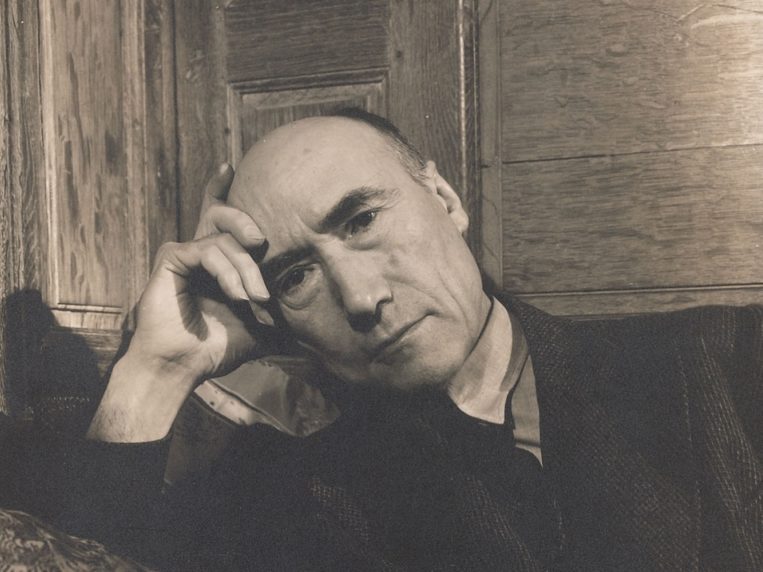

Donald Windham was born in 1920 in Atlanta. He was raised by his mother and aunt in a large Victorian home that served mostly as a painful reminder of the family’s prosperous past. By the time Windham reached adolescence, even the house was gone.

After high school, his mother found him a job in a Coca-Cola factory, where he rolled barrels through the warehouse and harbored dreams of becoming a writer. During his off hours, he fell in with a group of local artists and writers, including Fred Melton. The two became lovers and eventually left together for New York.

Windham and Melton shared several Manhattan apartments in the late 1930s and early 1940s. It was during this period that they befriended another young writer who would have a substantial impact on Windham’s life: Tennessee Williams. After meeting Williams, Windham was swept into New York artistic society, becoming friends with W. H. Auden, Tony Smith, Glenway Wescott, Paul Cadmus, and Truman Capote. Capote and Windham would remain friends throughout their lives.

Williams, already an experienced writer, also provided professional inspiration to Windham, who began writing short stories about his early years in Georgia. In the decades that followed, the two developed a friendship that included a co-written play, decades of correspondence, a novel by Windham about Williams, and a very public dissolution of their friendship in the 1970s.

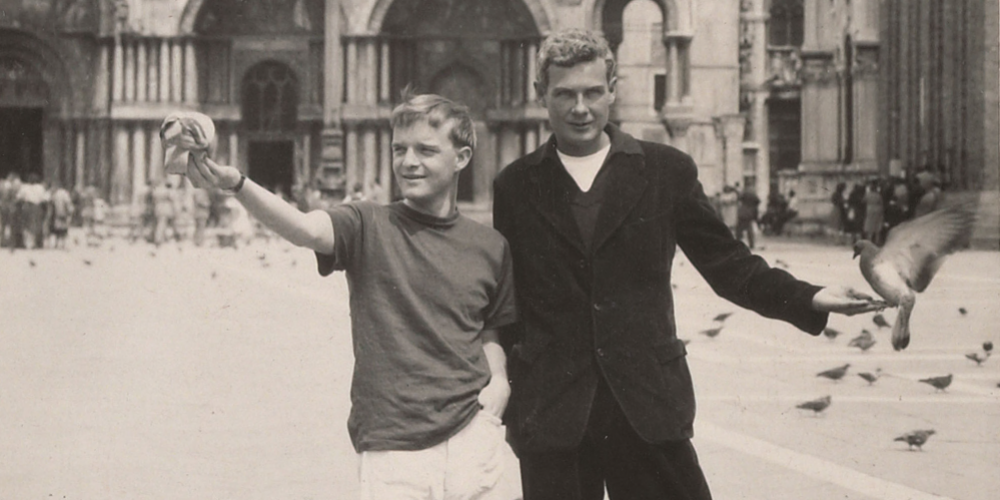

It was a chance meeting at Paul Cadmus’s studio, however, that proved to be of greater and more lasting importance. On a visit with Melton, Windham met a Princeton undergraduate named Sandy Campbell, who was modeling for one of Cadmus’s paintings. Windham and Campbell began a relationship that would last until Campbell’s death in 1988.

In 1942, while writing his first novel The Dog Star, as well as co-writing the play You Touched Me with Tennessee Williams, Windham began working as Lincoln Kirstein’s assistant at the magazine Dance Index. When Kirstein was drafted into the military in 1943, he handed the editorship over to the young writer.

As Bruce Kellner notes in Donald Windham: A Bio-bibliography, Windham soon enlarged his circle of acquaintances to include future Vogue photographer George Platt Lynes, artist Joseph Cornell, set designer Pavel Tchelitchew, choreographer George Balanchine, dancer Tanaquil Leclerq, and photographer and writer Carl Van Vechten.

When You Touched Me appeared on Broadway in 1945, the play earned enough to support Windham during a crucial period. He finished The Dog Star, which would not find an American publisher until 1950, despite having impressed both Thomas Mann and André Gide.

Windham’s work often found a more sympathetic audience in Europe than in the States. This changed for a time in 1960s, when he enjoyed his most sustained period of literary success. He published his novel based on the life of Tennessee Williams, The Hero Continues, in 1960, the same year that he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship.

He also began to publish a series of recollections of his childhood in the New Yorker. These eventually grew into a highly-regarded personal memoir, Emblems of Conduct, the success of which helped see into print his collection of short stories, The Warm Country, featuring an introduction by E. M. Forster.

This acclaim was short-lived, however. His novel Two People, about a married man who falls in love with a teenage boy, was savaged by critics. From then on, most of his books were brought out first in private editions, a few of which eventually found their way to mainstream publishers.

His relationship with Tennessee Williams took a darker turn in the 1970s, beginning with the publication of Williams’s memoirs. Feeling that the Williams depicted in the book bore little resemblance to the man he knew, Windham asked for and received permission to publish the letters he’d received from his friend. But when the letters were printed in a second edition by Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, Williams took offense to what he considered an unflattering presentation.

The argument spilled out into the editorial pages of the New York Times with remarkable ferocity. Lawsuits and recriminations followed for the better part of a decade before the friendship finally dissolved in acrimony.

The joys and vicissitudes of his long relationships with Williams and Capote are chronicled in Windham’s memoir Lost Friendships. Of his two famous friends he wrote, “As highly rewarded with celebrity and money as they were, each considered himself underappreciated . . . a personal example of the failure of America to value and recompense its artists.”

Windham, too, felt underappreciated, but his reputation as a writer has continued to grow. Emblems of Conduct is an exemplar of the creative nonfiction genre, and Windham's early and fearless representation of gay characters in his fiction has made works like Two People and the short story "Servants With Torches" essential reading in Queer Studies classes.

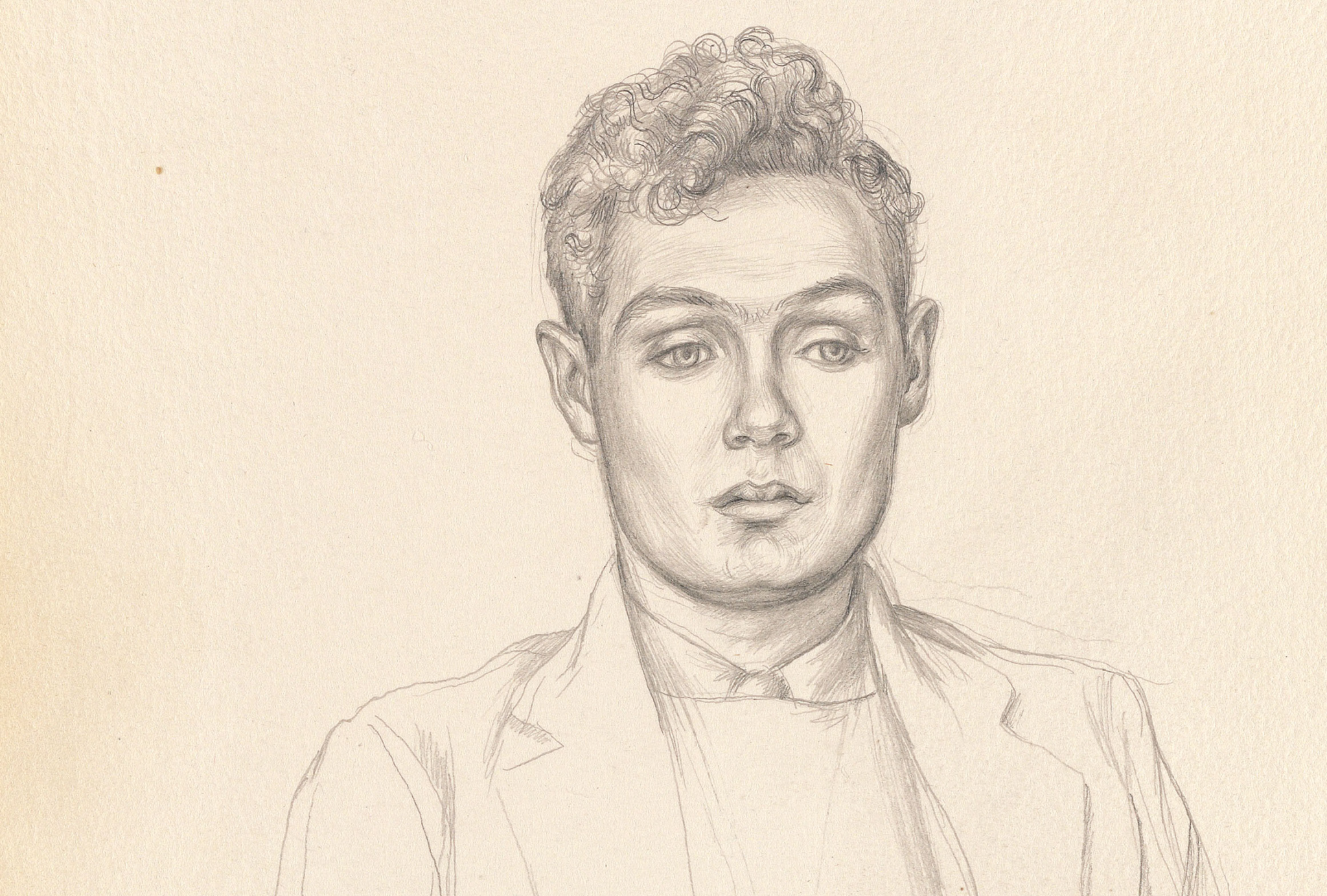

Sandy Campbell was born in New York City in 1922. His father owned a chemical manufacturing company that provided for the family. After attending the Kent School in Connecticut, Campbell studied at Princeton University, where he nourished his two abiding passions: acting and literature.

He soon made his way to the Broadway stage, where he landed roles in Life with Father, Spring Awakening, and A Streetcar Named Desire. Over two decades in the theater, he shared the stage with Marlon Brando, Spencer Tracy, Jessica Tandy, Tallullah Bankhead, Lynne Fontaine, Alfred Lunt, Lois Smith, and many others.

A chance meeting at the studio of Paul Cadmus brought him together with Donald Windham. The two remained romantic partners for the rest of Campbell’s life.

Alongside his acting ambitions, Campbell was a devoted reader, book collector, writer, and publisher. He began collecting at an early age and maintained the habit of finding the home address of an author, and writing to ask if he could send along his book to be signed.

His library included signed first editions by Graham Green, Vladimir Nabokov, William Faulkner, and E. M. Forster as well as books personally annotated by authors such as Katherine Anne Porter, Isak Dinesen, Alice B. Toklas, and Marianne Moore. Most of these are housed in the Windham-Campbell collection at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Campbell also wrote profiles of Nora Joyce, E. M. Forster, and the tandem of Lynn Fontanne and Alfred Lunt for Harper's Magazine. He worked for many years as a fact checker for the New Yorker, where he also wrote unsigned book reviews.

His book B: Twenty-Six Letters from Coconut Grove documents his time working on a revival of A Streetcar Named Desire alongside Tallulah Bankhead (the “B” of the title).

His longest-standing literary commitment was to Donald Windham and his writing. When Campbell’s acting career ended in the late 1950s, his focus turned to editing and publishing. Publishers began losing interest in Windham starting in the mid-sixties, so Campbell took it upon himself to make sure his work saw the light of day.

He contracted with the Italian publisher Stamperia Valdonega, and over the next twenty-five years brought out numerous exquisitely-crafted editions of Windham’s books, several of which found their way to large publishing houses, due in no small part to Campbell’s efforts.

When he died in 1988, Sandy Campbell left his estate to Donald Windham, with the tacit understanding that someday all or part of it would be used to create a prize to support writers.

The Windham-Campbell Prizes are the result.

Donald Windham and Sandy Campbell’s friendships stretched from Broadway and Hollywood to Europe and back. They counted as friends some of the most significant cultural figures of the mid-twentieth century. Both enjoyed the company of artists, writers, actors, directors, dancers, and sculptors. The Donald Windham and Sandy M. Campbell collection, an archive collected over more than fifty years, is rich with photos, mementos, and correspondence with many of these figures.